Agnieszka Trzaska-Śmieszek

Agnieszka Trzaska-ŚmieszekGroup proceedings (a Polish style of class action) have been functioning in the Polish system already for a decade. 19 July 2020 marked 10 years since the entry into force of the Act of 17 December 2009 on Pursuing Claims in Group Proceedings which introduced the class action into Polish procedural reality. How can these ten years be summarised?

In my opinion, this decade merits a positive assessment – obviously, not without certain reservations, yet summa summarum, it should be stated that the introduced provisions have been positively verified, especially in the form determined by two amendments (by the Act of 7 April 2017 on Amending Certain Acts to Facilitate the Seeking of Receivables which entered into force on 1 June 2017 and the Act of 4 July 2019 amending the Act – Code of Civil Procedure and Certain Other Acts which in the scope of the amendments to the Act partially entered into force on 21 August 2019 and partially on 7 November 2019). The Act itself may be an effective tool for the collective pursuit of claims, particularly so in the hands of lawyers and courts capable of its skilful application.

Undoubtedly, group proceedings (sometimes also referred to as class actions) have already become an inseparable element of the Polish procedural law system and it should be expected that year by year increasingly larger numbers of people will choose to pursue their claims in this mode. It seems, anyhow, that the class action institution is relatively popular in Poland. Perhaps these ten years did not see courts inundated with group proceedings on the scale fearfully anticipated before the introduction of provisions on class actions, but there are more of them than in other European countries (e.g. Sweden where no more than ten class actions have been initiated since 2005, or Italy).

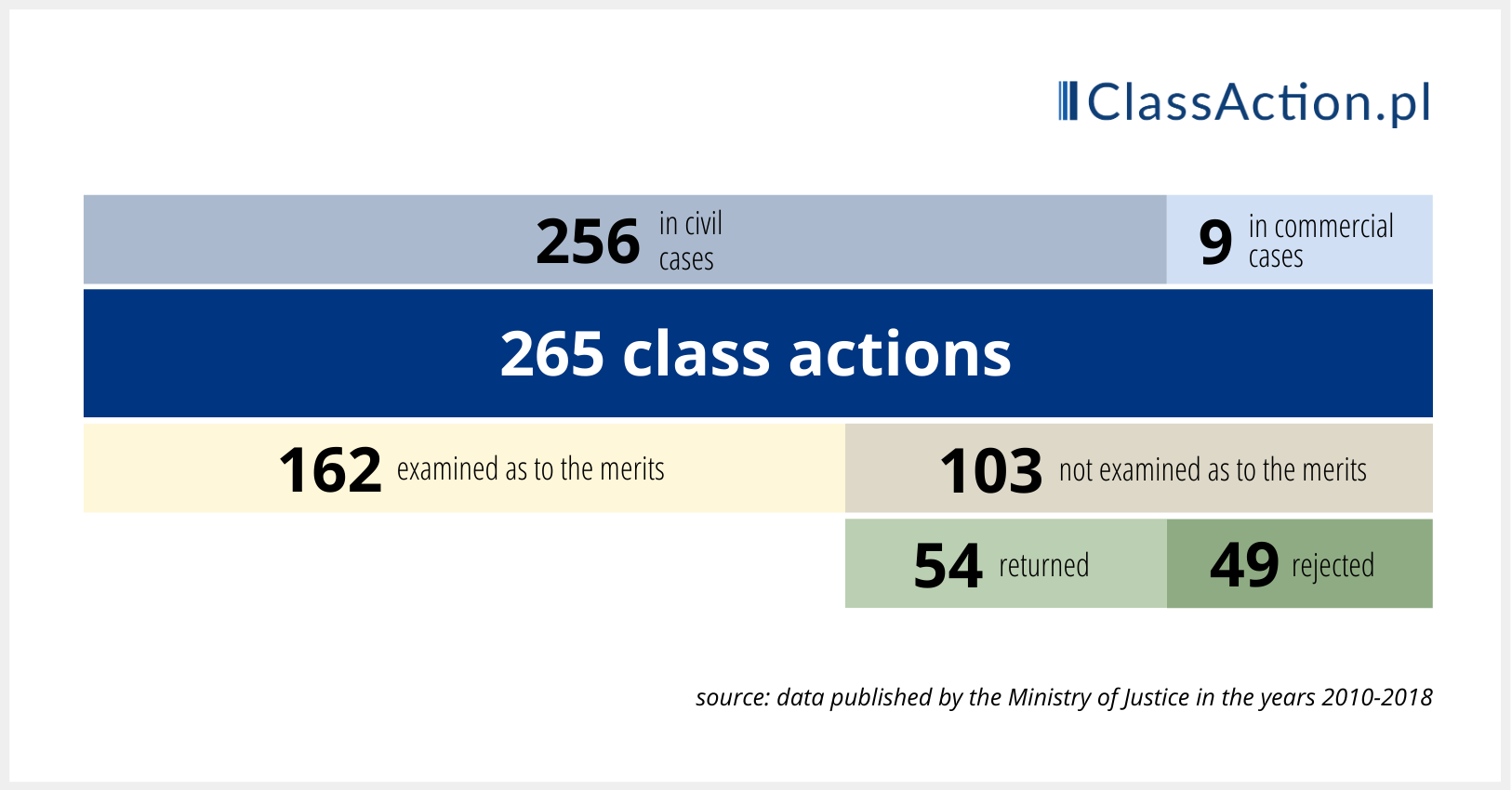

As follows from the data published by the Ministry of Justice in the years 2010-2018, jointly 256 class actions in civil cases and 9 in commercial cases have been brought before Polish courts, which give a total of 265 cases (nevertheless 103 cases from this number were not examined as to their merits – 54 class actions were returned, whereas 49 rejected).

source: https://isws.ms.gov.pl/pl/baza-statystyczna/opracowania-wieloletnie/

At present, more than sixty class actions are pending before Polish courts. What kind of cases are they? Diverse – the biggest part of cases is, obviously, consumer actions against entrepreneurs providing a variety of services, including actions against developers. Furthermore, another group of consumer cases is a series of actions against insurance companies (at least eleven proceedings) or a series of cases of holders of loans in Swiss Francs (frankowicze in Polish) (more than 12 proceedings). A substantial number of class actions were brought forth against the State Treasury (at least 9 proceedings).

Among the cases which are still pending, there are actions which were initiated in the first year of the Act’s entry into force, namely two cases related to negligence and omissions in the area of flood protection – the class action of Sandomierz residents affected by flood and the action of Kędzierzyn Koźle residents affected by flood. Initiated somewhat later, in 2012, the third action in this ‘series’ – the case of flood victims from the Płock area is still pending, as well. Only recently (15 July 2020) did the proceedings in one of the first initiated cases of holders of loans in Swiss Francs (frankowicze in Polish) conclude – “Grupa na Bank” vs. mBank, and this was concluded only because the bank withdrew the appeal. Ten years is no doubt way too long even in complicated cases, yet this is the reality of conducting cases before Polish courts. What is symptomatic, for the needs of resolving of all the quoted cases, the courts requested expert opinions, and – as is well known not from today – the issue of the institution of court experts, remaining unsolved for many years, substantially contributes to prolixity of proceedings.

This is because group proceedings grapple with the same ailments as those encountered by parties and their counsels in civil cases in general, but also in other court proceedings – i.e. first and foremost excessive lengthiness or the downright prolixity of proceedings. Unfortunately, the justice administered by the Polish judiciary (administration of justice system) takes a long time, and in the group proceedings waiting period is sometimes longer than in individual cases since group proceedings are usually complicated cases. Bearing in mind that the prolixity of court proceedings in Poland is considered to be systemic, the reasons for the lengthiness of class actions is to be sought in the same factors which impact the prolixity of proceedings in general, while not in the very form of the provisions of the Act on Pursuing Claims in Group Proceedings. Moreover, the provisions of the Act which may have led to the unnecessary protraction of group proceedings were amended by the amendment of the Act of 7 April 2017. In the first years of functioning of the collective redress mechanisms, an additional factor that may have contributed to the lengthiness of proceedings was no doubt its legislative novelty in the Polish legal order, and hence the need for judges and other lawyers to learn how to apply the new rules of procedure departing from the traditional, individualist take on litigation.

Apart from this, over the course of these ten years, a change in the approach presented by Polish courts towards the new collective redress mechanism could be observed. Undoubtedly, the year 2015 when three important judgments of the Supreme Court heard in class action mode – most importantly the decision of the Supreme Court of 28 January 2015, file ref. No. I CSK 533/14, issued in the case A group of relatives of individuals who sustained damage in the construction catastrophe of the Katowice International Fair hall – may be considered the turning point. Initially, the majority of courts presented a rather reluctant approach towards group proceedings and sometimes they followed a rather rigorist interpretation of prerequisites conditioning the admissibility to be heard in group proceedings – a substantial number of actions were rejected or returned. Starting from 2015, a trend to the contrary could be seen – larger amounts of cases were positively certified at the first stage – including an entire series of cases against insurance companies or Swiss franc-related cases. Observation of this practice persuaded the legislator in 2017 to introduce an amendment to the Act of 17 December 2009 on Pursuing Claims in Group Proceedings; whereby the new provisions applied to cases initiated after 1 July 2017, hence the facilitating and streamlining ‘effects’ are still to be awaited.

Nevertheless – throughout the decade of the Act’s being in force, several important cases were successfully resolved in a final manner. In first order, it is worth indicating the case related to the mass building disaster of the International Katowice Fair. The collapse of the International Katowice Fair exhibition hall no. 1 in Chorzow on 28 January 2006 was the biggest construction catastrophe in Poland’s history. The incident providing the background of these proceedings turned out to be an impulse for the Polish legislator to engage in works on a draft act. The first statement of claims of the group of 16 injured parties filed in February 2011 was rejected in a final manner. The reason for its rejection was the fact that it included claims for the protection of personal rights – which are excluded from the objective scope of the Act. Only the second statement of claims filed on 30 January 2013, led the group to winning the case. The history of both of these cases is described on the portal – case no. 1, case no. 2.

Moreover, at least five cases against developers concerning the improper performance of contractual obligations were concluded (see. history of the cases with proceedings concluded by a final content-related settlement):

Furthermore, the following cases were concluded in a final manner:

The analysis of the course of the proceedings in the above-mentioned cases leads to the conclusion that group proceedings are more efficiently prosecuted by smaller courts where such cases are heard faster than, for example, by the particularly besieged Regional Court in Warsaw. It may, of course, provide an impulse for discussion whether class actions should not be heard by specialised courts or use a faster path of examination – bearing in mind that one class action replaces at least ten or even several thousand individual cases as can be seen if only in Swiss franc-related cases where groups include large numbers of members.

In summary, the solutions adopted 10 years ago have generally proved their worth and, although one may have reservations as to the effectiveness of group proceedings due to their duration, in principle, the low effectiveness results not from the very shape of the provisions (especially after the amendment of the Act of 7 April 2017), but from the same systemic reasons that cause the lengthiness of court proceedings in general. The analysis of the subject matter of individual group proceedings leads to the conclusion that undoubtedly the Act has increased access to the administration of justice, because – if there were no such collective mode of pursuing claims – the majority of parties who are members of groups in individual cases would not decide to pursue their claims individually (particularly in tort cases and in actions against the State Treasury).